Social Data Science

Statistical Reasoning: Interpreting Patterns in Data

Goals

- Find out whether data automatically tells us what is true or not

- Identify patterns in data and describe what they show

- Distinguish descriptive, predictive, and causal claims

- Ask better questions when someone makes a data-based claim

Why statistical reasoning matters?

- Intellectual skill: Reason carefully about patterns in human behavior

- Academia: Read, interpret, and contribute to social science research

- Policy: Evaluate evidence behind decisions that affect society

- Private sector & life: Use data responsibly to anticipate outcomes

“According to data…”

Does data speak?

- Common claims:

- “The data says X causes Y”

- “According to data, A is better than B”

- Implied: data reveals objective truth

- Reality: data requires interpretation

Variables

- Characteristics that vary

Types of Variables

- Nominal/categorical: Cannot be ordered

- Region

- Ordinal: Ordered

- Very liberal < Liberal < Moderate < Conservative < Very conservative -Numerical: Ordered + equidistant

- Age, GDP, number of casualties

Practice

Varieties of Democracy’s regime type measure:

- 0: Closed autocracy – No multiparty elections

- 1: Electoral autocracy – De-jure elections but not free and fair

- 2: Electoral democracy – Free and fair elections with some flaws

- 3: Liberal democracy – Free and fair elections guaranteed

Political Regimes

Interactive Map

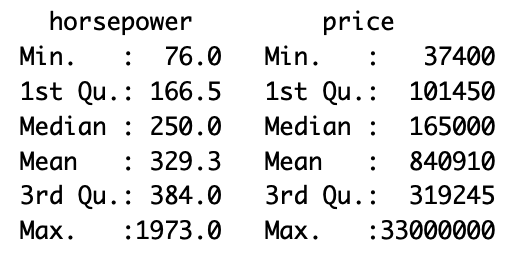

Descriptive Statistics

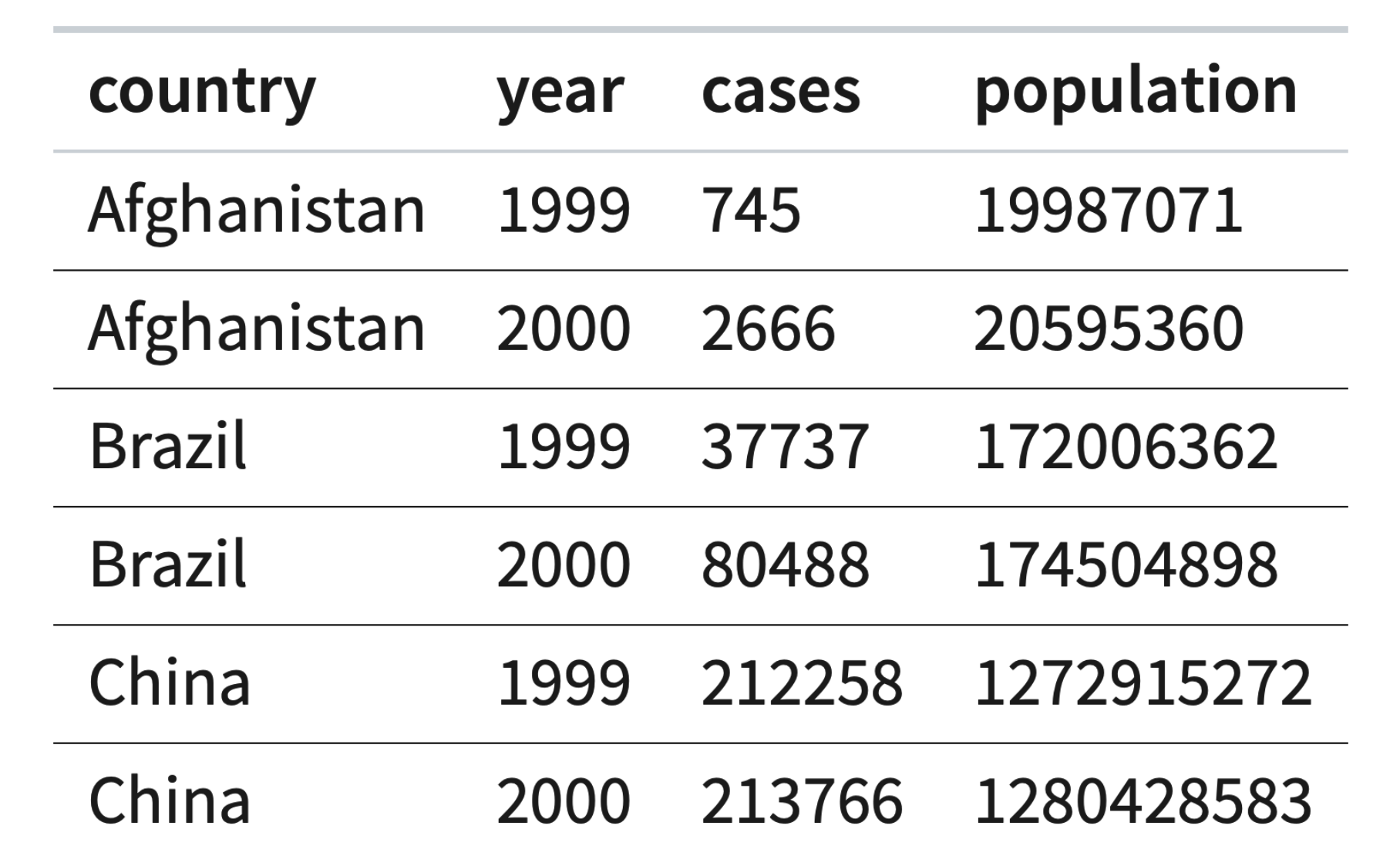

Summarizing Patterns: Categorical data

- Counts / frequencies: How many observations fall in each category.

- Percentages / proportions: Useful to compare groups.

- Mode: The most common category

Source: qatarcars

Source: qatarcars

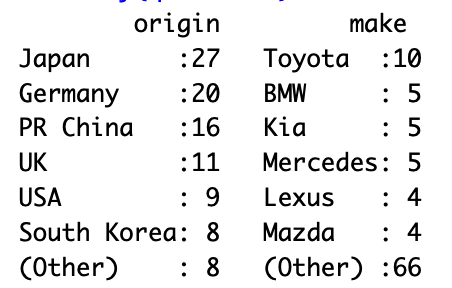

Descriptive Statistics

Summarizing Patterns: Numerical data

- Measures of central tendency:

- Mean (average): Add values, divide by count

- Median: Middle value when ordered

- Mode: Most common value

- Measures of spread / variability:

- Range: Difference between max and min

- Standard deviation

Source: qatarcars

Source: qatarcars

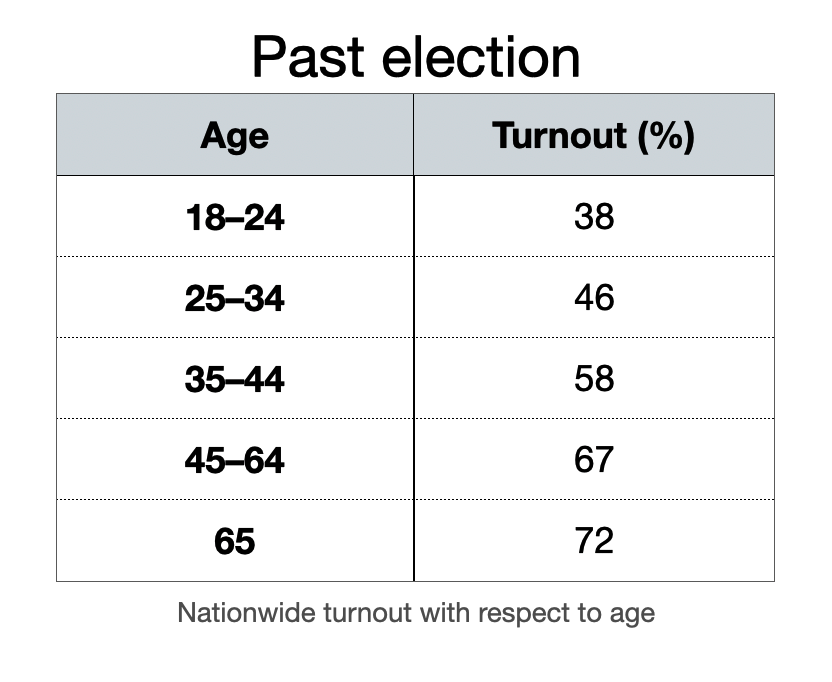

Predictive Reasoning

Can we forecast outcomes?

- Use patterns to predict an outcome

- Example: Next election, would we expect a high or low turnout at a university town?

- What if we want to know why?

Causal Inference

Does X cause Y?

- X: Independent variable

- Y: Dependent variable

- Causal claims are everywhere

- The ultimate question:

- does changing X change Y

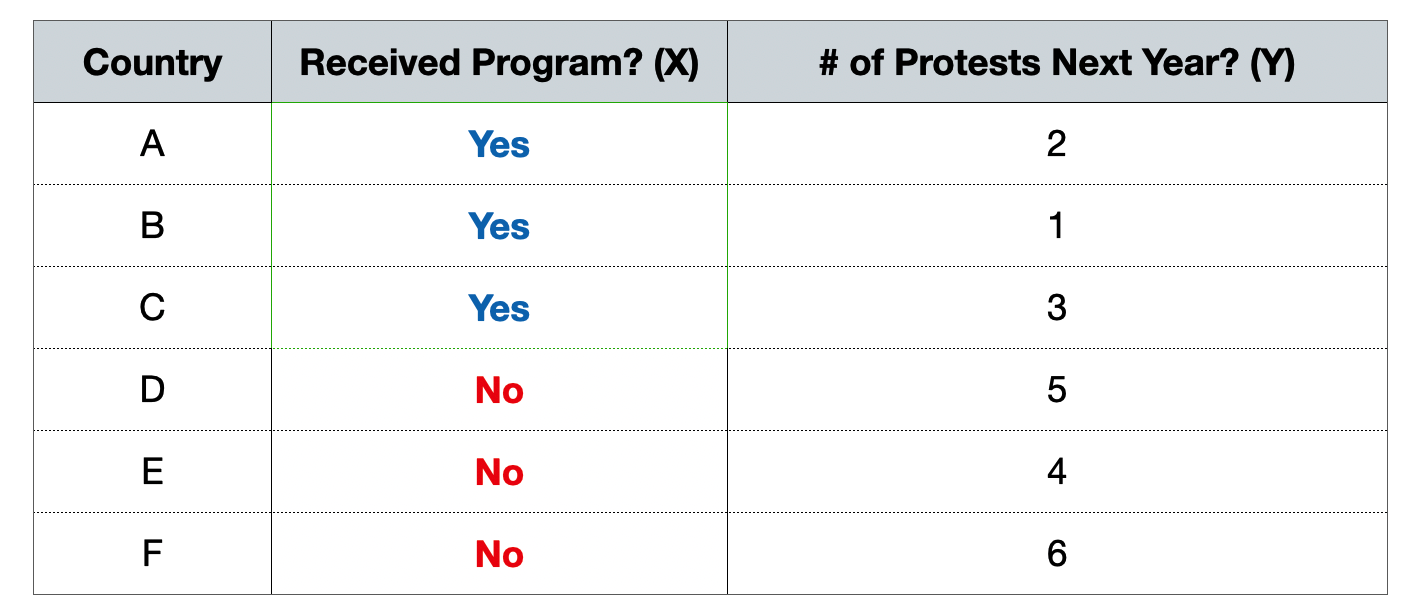

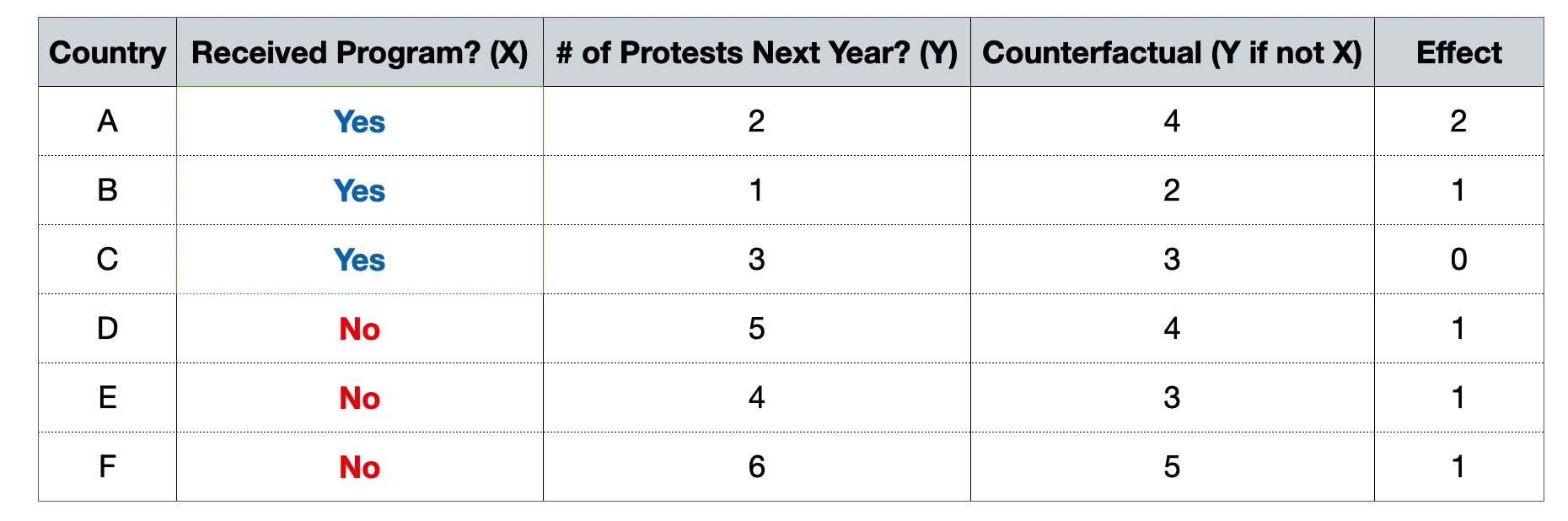

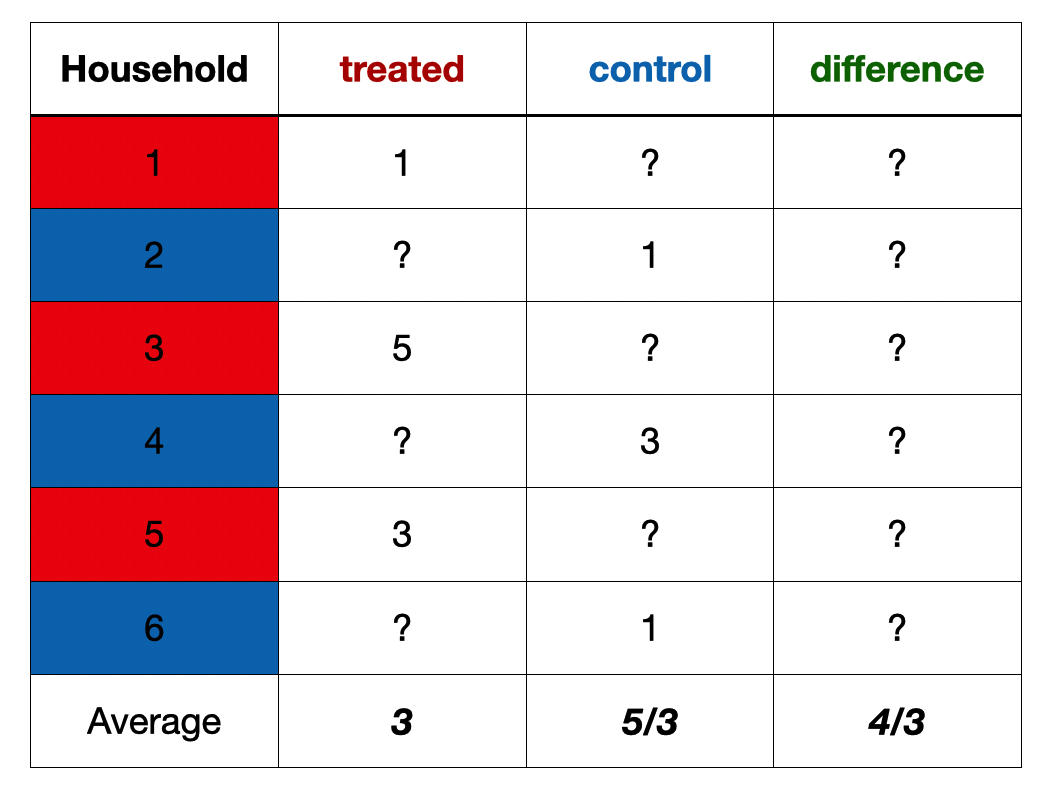

Do democracy promotion programs reduce protests?

- Average protests if received program: (2+1+3)/3 = 2 → fewer protests

- Average protests if no program: (5+4+6)/3 = 5 → more protests

- what if we knew both worlds?

Counterfactuals

What would Y be if X did not change/take place?

- If Trump did not win 2024 elections, would Maduro still be in power?

- If it wasn’t for Qatar, would Messi ever win the World Cup?

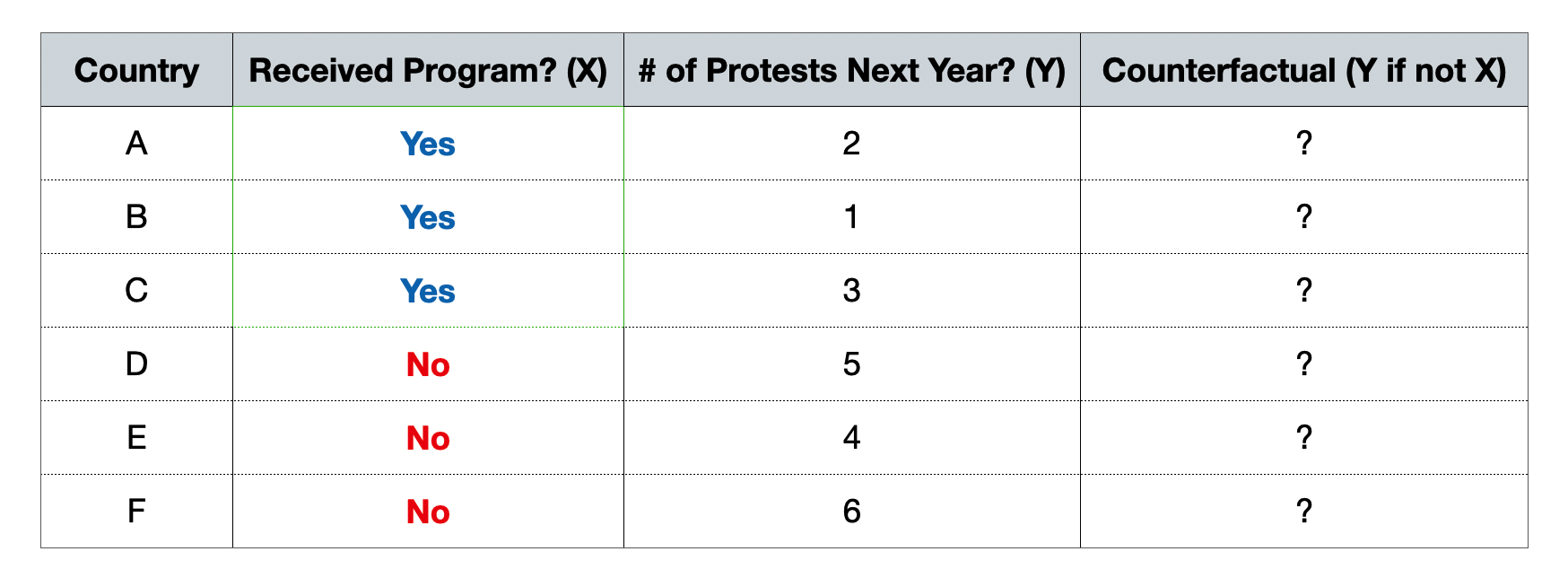

Potential Outcomes & Counterfactuals

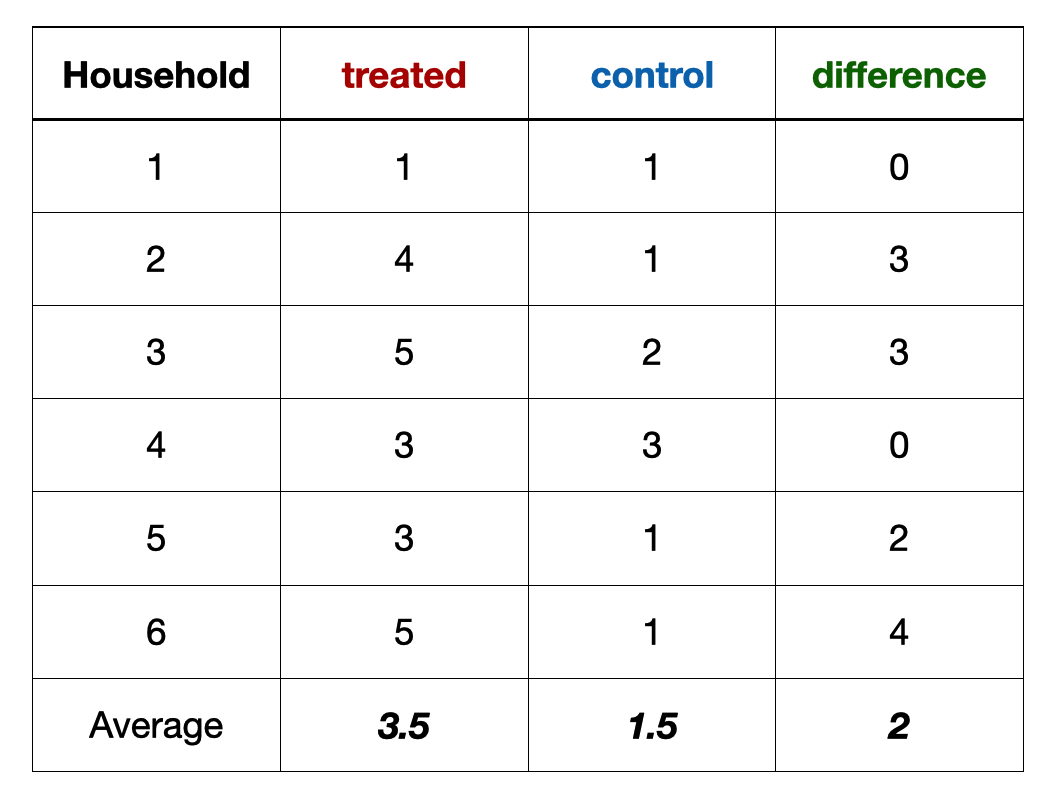

- Going back to the example, we do not know the counterfactuals.

- But let’s assume we do know them…

Potential Outcomes & Counterfactuals

- Average effect for countries that received program: (2+1+0)/3 = 1

- Average effect for countries that did not receive program: (1+1+1)/3 = 1

Causal Inference

Does a change in X cause a change in Y?

- Patterns alone are not enough

- Observations that are treated and not treated tend to be systematically different: Selection bias

- Without counterfactuals, it is difficult to make causal claims

How do we detect counterfactuals?

Bad news: we can’t

Bad news: we can’t

Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference: We never observe the counterfactual

Good news: we can predict them

Good news: we can predict them

Causal inference = imputing the counterfactual and estimating the effect

Imputing the counterfactual

- Qualitatively

- Case studies

- Quantitatively

- Experiments

- Observational studies

Experiments

Gold standard

- Random assignment ensures no selection bias

- Isolate the effect of X on Y

Let’s think about this intuitively

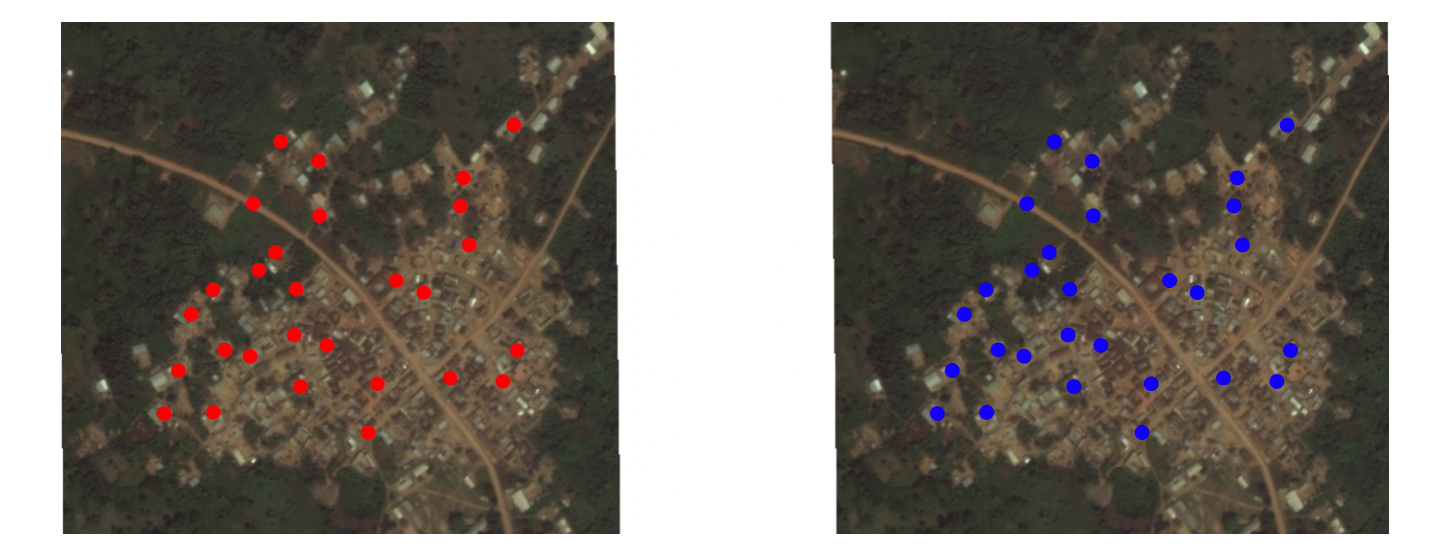

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

- How can we close persistent gender gaps in political participation?

- Male household members as “gatekeepers” of women’s participation

- Targeting women -> no effect

- Targeting male household members -> increase in women’s turnout

Let’s think about this intuitively

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

Figure: A random sample of households in Pakistan

Let’s think about this intuitively

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

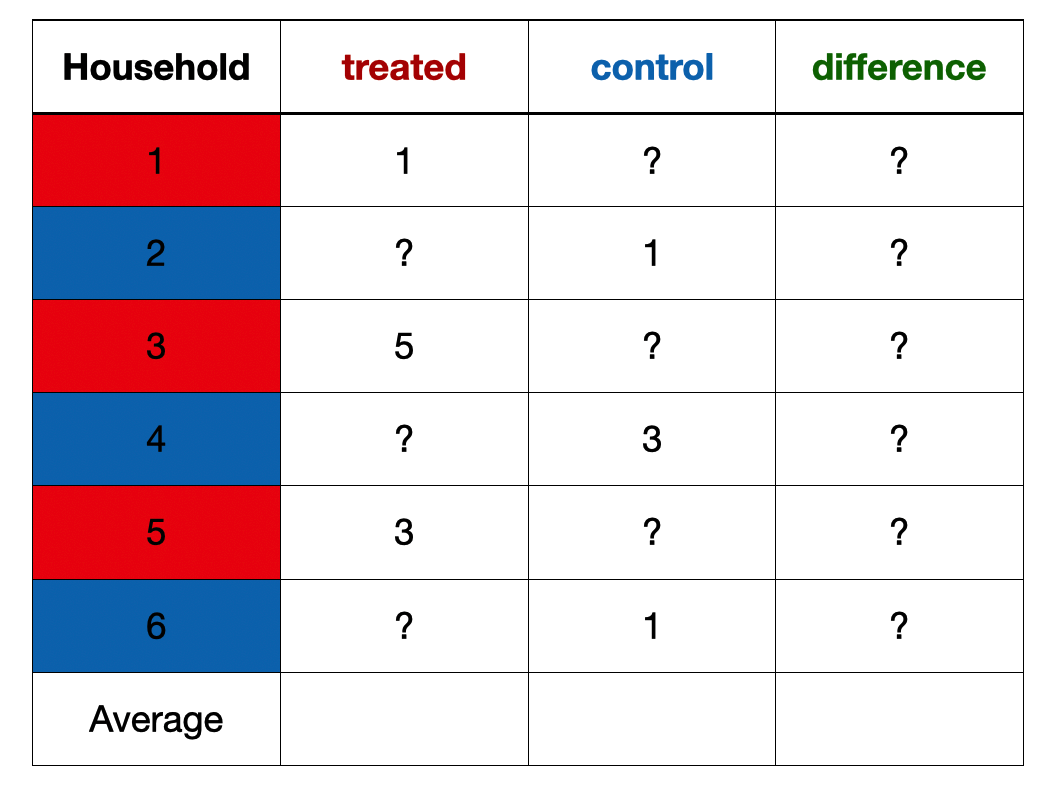

Figure: Each household has potential outcomes treated and control

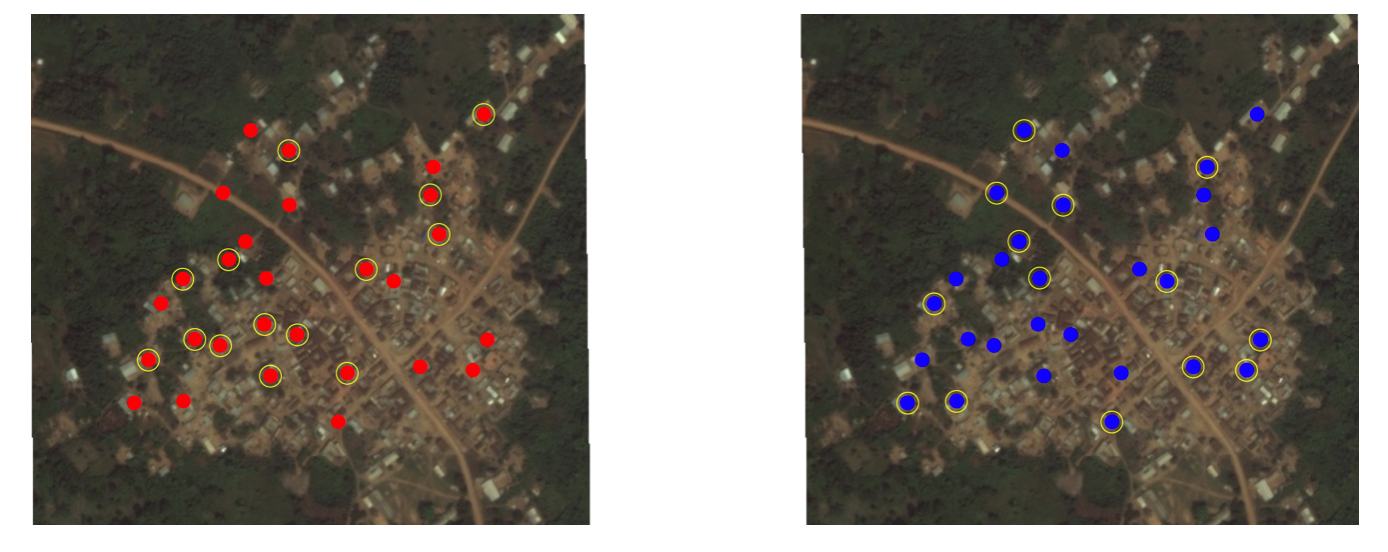

Let’s think about this intuitively

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

When you assign a household to treated, you are realizing the household’s potential outcome under treatment

When you assign a household to control, you are realizing the household’s potential outcome under control

Let’s think about this intuitively

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

Random assignment to treated or control means we’re drawing a random sample of these potential outcomes

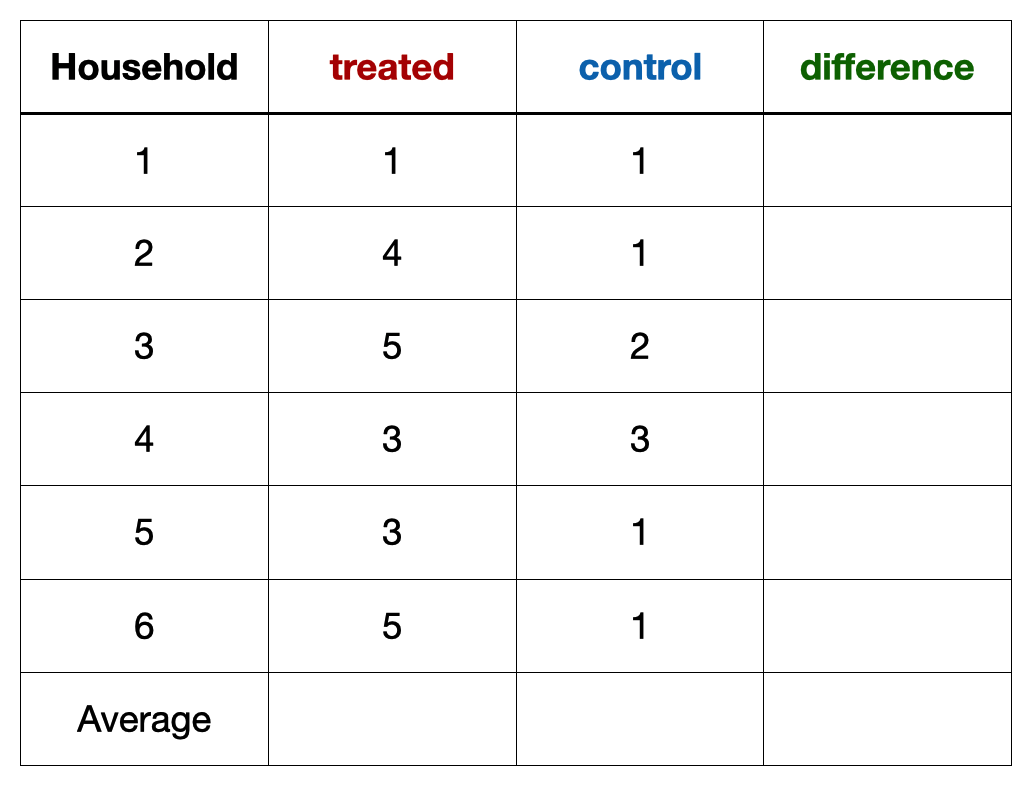

Exercise

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

Exercise

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

Exercise

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

Exercise

An example from a field experiment in Pakistan (Cheema et al. 2022)

Experiments

Limitations

- Why not run experiments for everything?

- Practical constraints

- Cost, time, scale

- Feasibility

- Cannot randomly assign many social conditions

- Ethical considerations

- Harm, consent, fairness

- Practical constraints

Observational Designs

When we cannot run experiments

- Many social questions cannot be randomized

- Democracy, migration, welfare, education

- Policies are not supposed to be not assigned at random

- Welfare is not given to the rich

- This creates selection bias

Matching

Comparing similar units

Idea: Compare units that are similar in important ways, except for whether they received the treatment

Example: Do UN peacekeeping missions reduce civilian deaths?

- Problem: Peacekeepers are sent to more violent conflicts

- Solution: Compare conflicts with similar violence levels

- Some with peacekeepers | some without

Discontinuity Designs

Comparing units near a cutoff

Some policies use clear rules or thresholds

- Elections, Welfare programs

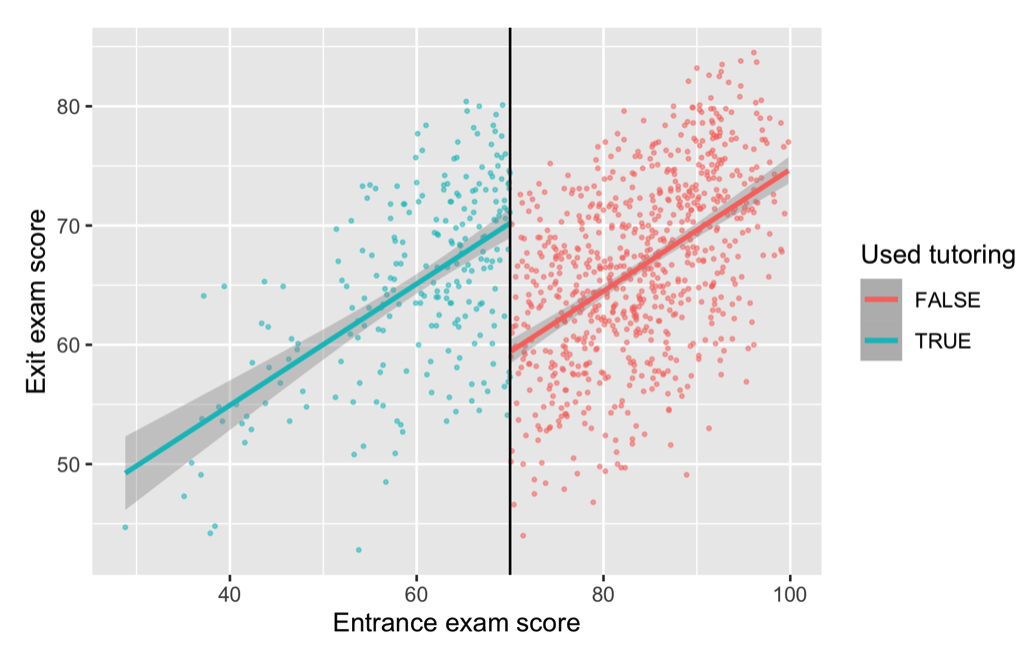

Example: Does tutoring improve student performance?

Problem: Students who do and do not get tutoring may already be different

Policy: Students scoring 70 or below get tutoring

- Compare students just below and just above 70

Discontinuity designs

Compare units around a threshold

Source: Andrew Heiss

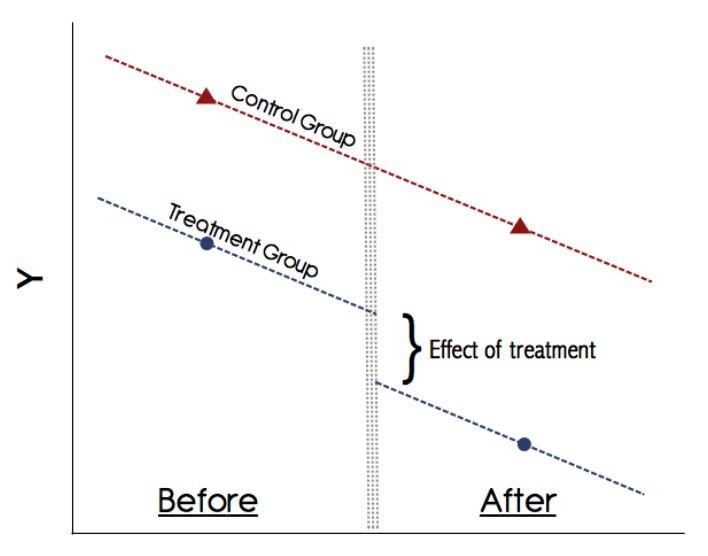

Difference in Differences

Comparing changes over time

- Idea:

- Compare how outcomes change over time between a treated group and a similar control group

- Focus on differences in trends, not levels

Difference in Differences

Comparing changes over time

- Example: How do sanctions affect human rights violations?

- Two countries:

- One sanctioned (treated)

- One not sanctioned (control)

- Key assumption:

- Both countries followed similar trends before sanctions

- Two countries:

Difference in Differences

Compare units that follow similar trends the treatment

Source: Kevin Goulding

Other designs for observational data

- Instrumental variable

- Synthetic control

- Shared goal: imputing the counterfactual using appropriate the design

Takeaways

Why statistics matters

- Data don’t speak for themselves: they are produced, measured, and interpreted by humans.

- Statistical reasoning is powerful: bad data, poor comparisons, or naive interpretation can mislead.

Takeaways

Why learn?

- Policy relevance: make sense of interventions and their consequences.

- Social science literacy: read and critique academic research confidently.

- Real-world decision-making: informed skepticism is a marketable skill anywhere data are used.

Thank You

Questions & Discussion

- Thank you for your attention!

- Feedback, questions, connections: olgahan@brown.edu